Fossil Fuel Growth Doesn't Mean We're Not Making Progress

Exponentials Look Darkest Before The Dawn

Deployment of solar power, wind power, electric vehicles, and other green technologies is accelerating rapidly, and yet fossil fuel consumption hasn’t really started to decline. For instance, here is natural gas consumption1 over the last 30 years:

Understandably, this causes a lot of people to worry – are we making any progress at all? It’s easy to look at a graph like that, and think we’re going keep pulling carbon out of the ground until there’s nothing left. If all the work so far hasn’t made a dent, what hope can there be?

Fortunately, this isn’t the right way to think about it. If we’re going to have any hope of holding warming to a reasonable level, climate-friendly solutions are going to have to grow exponentially – and in an increasing number of sectors, that’s exactly what is happening. In an exponential transition, there won’t be a visible dip in fossil fuels until the game is almost over. When the shift occurs, it can be very rapid, and seem to come out of nowhere. This graph doesn’t mean we’re losing; it just means we haven’t won yet.

What An Exponential Transition Looks Like

Google defines exponential as “becoming more and more rapid.” In mathematical terms, exponential growth means that growth is constant as a percentage, rather than being constant in absolute terms. For instance, if we install 100 gigawatts of solar PV capacity each year, that’s “arithmetic” growth. If capacity increases by 25% each year, that’s exponential growth. Arithmetic growth continues steadily; exponential growth accelerates: the more you have, the more you add.

Exponential growth appears frequently in the real world. Covid spreads exponentially, because as more people get infected, more people are spreading the virus. New technologies often grow exponentially, because more buyers generate more revenue to build more factories.

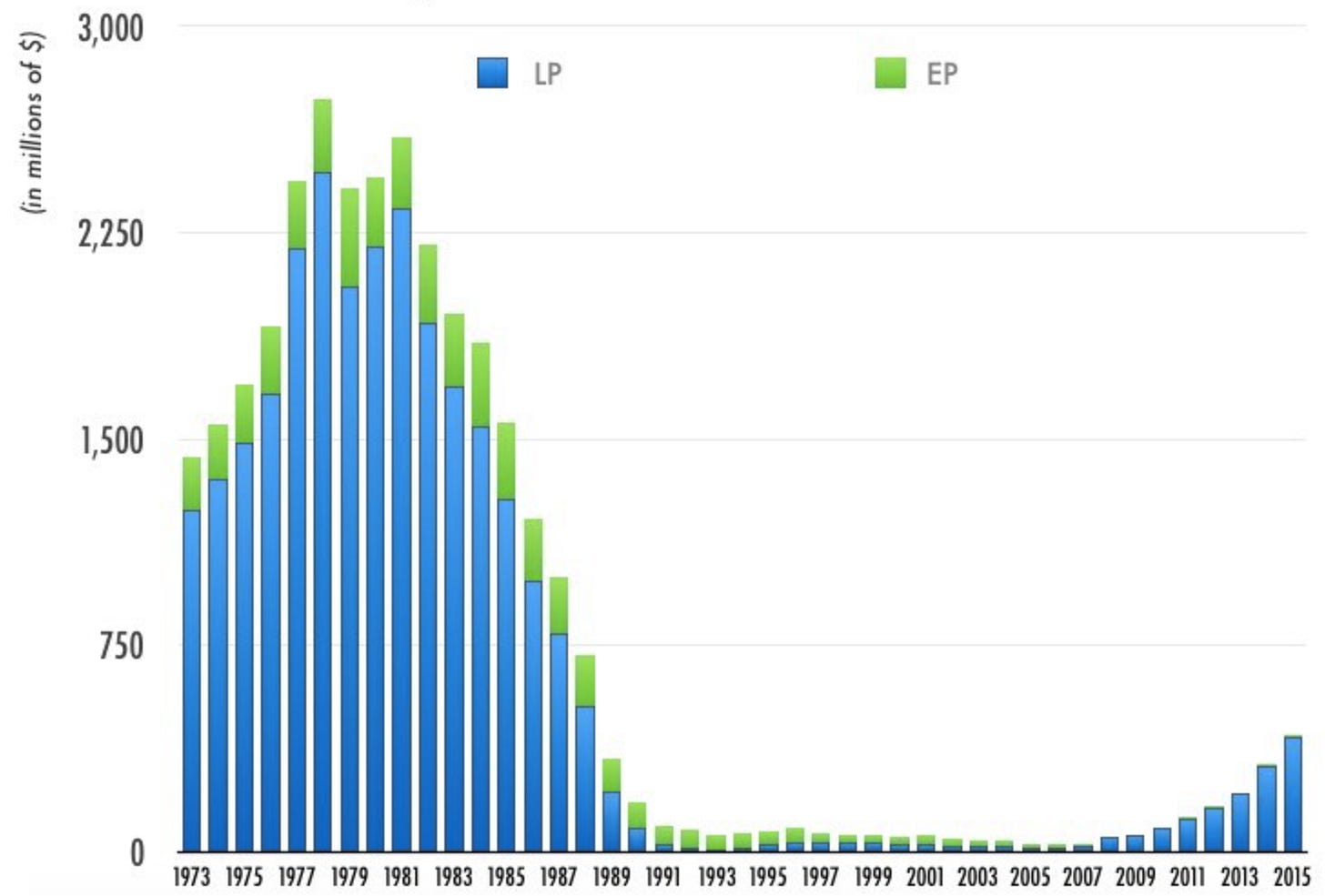

When graphed, exponential growth often seems to feature a “tipping point”, where the trend suddenly becomes obvious. Check out this chart of vinyl record sales (source):

In 1981, things looked good. Sales had been increasing steadily, aside from a hiccup in 1979, and were approaching a record high. And yet over the next ten years, the vinyl market utterly collapsed, replaced by CDs and cassettes. The transition to the new thing (CDs) wasn’t visible in sales of the old thing (vinyl records) until suddenly it was very, very visible indeed.

For another example of an exponential transition, consider the early days of the Covid epidemic. Here is the number of Americans who had not had Covid2:

Doesn’t look like much is happening, does it? Now look at the number of people who had gotten Covid, in the same time period. This is the same exact same data, but in this form it’s a lot more revealing:

In the early stages of exponential growth, there’s not much impact on the big picture. A graph of the status quo – vinyl sales, uninfected Americans, or fossil fuel consumption – won’t show anything happening. And yet that “invisible” early growth can set the stage for a sudden, tectonic, collapse-of-the-vinyl-album transition – or a catastrophic pandemic. By the time the status quo starts to visibly shift, the game is almost over.

How This Might Play Out In The Energy Transition

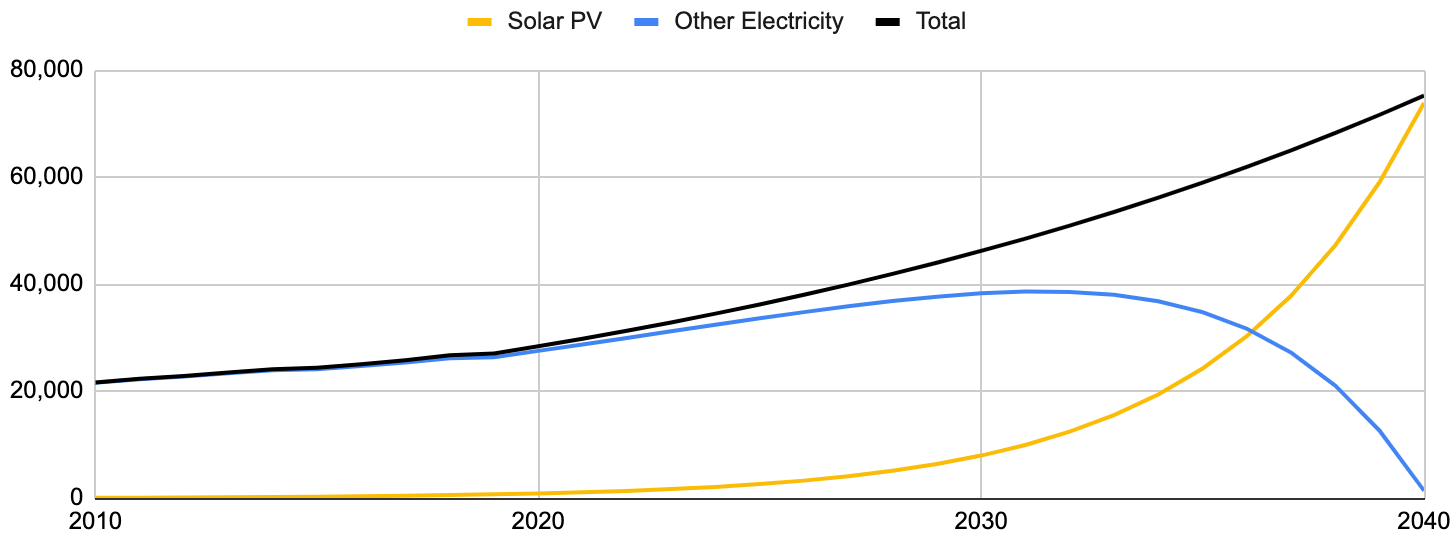

The hidden-progress effect is especially strong when the overall system is growing, because that growth helps to mask any incipient decline in the old solution. To illustrate, I built a simple toy model of the growth in solar power. The following graph shows actual global electricity production figures for 2010-20193, and then projects steady exponential growth4:

You can see that through 2033, non-solar generation hasn’t really started to decline. Now here’s the exact same scenario, carried seven years farther:

Boom! In just seven years, the exponential growth goes from no-visible-impact to world domination.

To be clear, this is an oversimplified scenario. The real transition involves multiple clean energy sources, growth rates won’t be as steady as I’ve used here, the timing is probably off, and I’ve only covered electric power. But you can see that accelerating growth in clean energy can result in fossil fuels undergoing a very rapid transition from continued growth to falling off a cliff. To judge progress, we need to look at the growth in clean energy, rather than waiting for fossil fuels to decline.

The Real Signals To Watch

All exponential trends peter out eventually. The initial Covid wave peaked after infecting less than 5% of the country. Even vinyl has… somehow made a comeback? Just because renewables are growing exponentially today, doesn’t mean the green transition is assured. Here are the key questions we should be asking:

For each new solution that we’re counting on – wind turbines, heat pumps, green hydrogen, the whole long list – how quickly is it growing?

Is that growth increasing exponentially?

How far can that growth continue? What barriers will eventually be reached?

Solar power has plenty of room to grow, but it’s not well suited to all locations, and must be paired with other sources for cloudy weather, nights, and short winter days. Other green technologies will face their own barriers and limits. To understand whether we’re on course to eliminate fossil fuels, we need to understand where those limits are.

How To Win

Just as we can’t evaluate progress by looking at sales of fossil fuels, we can’t improve progress by impeding sales of fossil fuels. To win, we need to foster the exponential growth of green solutions:

In sectors where no clean solution has achieved exponential growth, we need to develop new ideas, like the electric cargo ships with swappable batteries I wrote about in March.

In sectors where exponential growth is occurring, we need to look for potential limits. We can then either find ways to circumvent those limits, or foster new solutions that can work where the current solution won’t – like advanced geothermal or nuclear power for dark, windless nights.

Anything that accelerates growth is always helpful, whether it’s improved technology, new business models that lower friction, policy incentives, or awareness campaigns. Anything to spin the flywheel faster.

We really are going to displace fossil fuels. We just won’t see it coming in advance. People who were paying attention to the math could see that climate change was coming, long before the effects were visible. Today, the math tells us that fossil fuels are on borrowed time. The transition will take longer than we’d like, and we need to keep pushing to accelerate it. But renewables are growing exponentially, and that is what it takes to win.

Source: iea.org. Here are links to their data for oil, natural gas, and coal. The oil and coal graphs show a bit more up-and-down, rather than the steady rise of natural gas, but none are yet showing sustained decline.

This is based on estimates of total infections, not just reported infections. Taken from the excellent work at covid19-projections.com, specifically the raw data here.

Data from iea.org again: Electricity generation by source.

Solar power averaged a 37% annual growth rate over the previous decade. Going forward, I model 25% annual growth. For total electricity generation, the previous decade averaged 2.4%, and going forward I model 5% (on the assumption that electrification will boost demand). These are not intended as serious projections.