John Doerr Has a Plan

It’s been 40 years since I wrote my last “book report”, and I didn’t much enjoy it then, but here I am back in the saddle. Speed & Scale, a new book by venture capitalist John Doerr and Ryan Panchadsaram, presents a soup-to-nuts plan for bringing the global economy to net zero emissions by 2050. There is a disappointing lack of insight into the thinking behind the plan, but still the book serves as an excellent, comprehensive overview of climate change mitigation. It also sparks some interesting questions about the tradeoffs inherent in a project of this scope.

If you’re not familiar with John Doerr, I’ll just quote Wikipedia as noting that he “has directed the distribution of venture capital funding to some of the most successful technology companies in the world, including Compaq, Netscape, Symantec, Sun Microsystems, drugstore.com, Amazon.com, Intuit, Macromedia, and Google.” It also notes that he had “a net worth of $12.7 billion as of March 3, 2021”.

So, pretty successful venture capitalist. Does that qualify him to solve the climate crisis? Of course not; but based on the book, it does seem to have provided him with a few useful tools and attributes. Notably:

Experience in planning complex, novel ventures

Ability to confront audacious goals and massive scale without flinching

Access to everyone from Al Gore and Bill Gates to the CEO of GM and the Chief Scientist of the Environmental Defense Fund

Doerr summarizes his interest in the environment as follows:

In 2006, I was moved by Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. Then I was challenged by my teenage daughter: “Dad, your generation created this problem. You better fix it.”

This is the second time in recent weeks I’ve heard about a major tech executive being pushed into climate activism by his daughter(s). Supposedly, Microsoft’s aggressive campaign to reduce their climate impact stems in no small part from Steve Ballmer getting beaten up by his daughters. Maybe it’s time for DACC: Daughters Against Climate Change.

What Does A Plan For Climate Change Look Like?

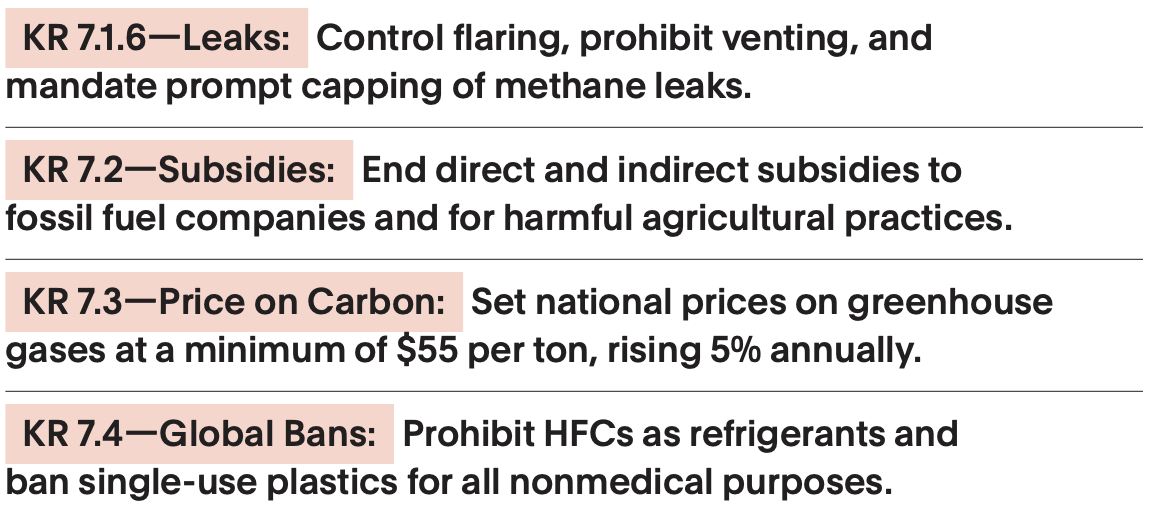

This book is presented as “A comprehensive plan to tackle one of the most vexing challenges in human history”, and he’s not kidding about the “comprehensive” part. Here’s a snippet from the subsection on “Policy Needed in the United States”:

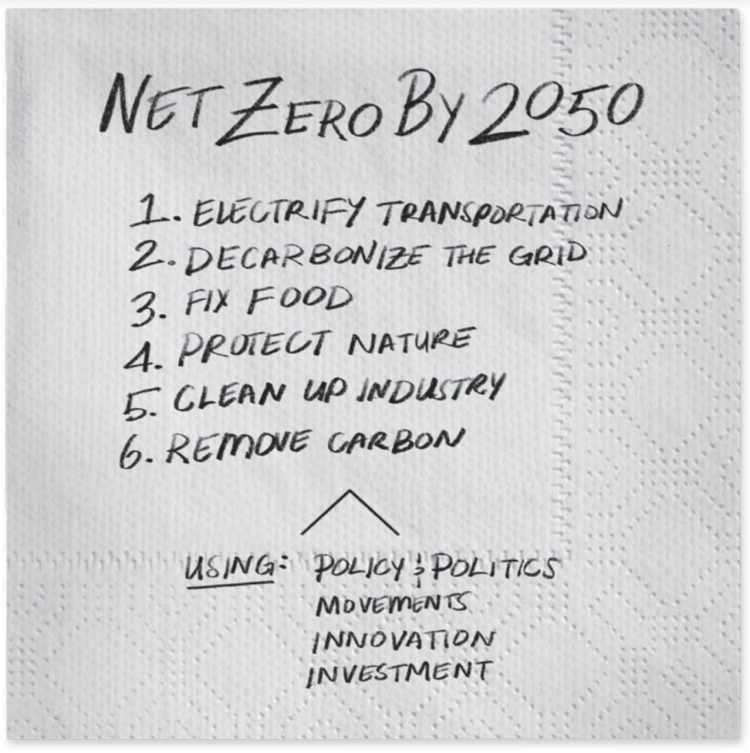

The plan is structured into six sectors – transportation, electricity, etc. – and four channels of activity. He summarizes it for us on a cocktail napkin, by reference to an episode in March 1942 where FDR sketched his plan for winning World War II. Here’s Doerr’s napkin:

Doerr starts with the number 59: the number of gigatons of CO2 (or equivalent) emitted each year. He breaks this down into five categories – transportation, electricity, agriculture, natural sources, and industry – and assigns a reduction target to each. This leaves 10 Gt/year of hard-to-eliminate emissions, which he balances by calling for removing that amount of CO2 directly from the atmosphere (a process known as “direct air capture”). Each category is broken down into subcategories, with reduction targets for each, like this:

In summary, the plan consists of:

A breakdown of global emissions, down to the level of “Buses & Minibuses” or “Manure Management”.

Reduction targets and timelines for each subcategory.

A similar set of detailed goals for policy, public activism (“movements”), innovation, and investment. For instance, “Increase zero-emissions project financing from $300 billion to $1 trillion per year”.

Most of the book consists of discussion. For each topic, Doerr attempts to explain why it is important, why there is hope for addressing it, and provide stories from people who are already working to drive change. For instance, Mary Barra (the CEO of GM) discusses GM’s transition to electric vehicles.

Why Plans Matter

Is a plan like this actually useful? In the context of climate change, there are far too many unknowns for any plan to hold up in detail. For instance: How quickly can new technologies be refined and deployed? How quickly will governments put new policies in place, and how effective will those policies be?

Equally important, it is not as if the world is in any position to coordinate execution on a detailed global plan. Even if all countries had similar politics (hah), understanding of the problem (stop it), and motivations (seriously, you’re killing me here), climate solutions will not be one-size-fits-all. Variations in natural resources, industrial capabilities, cultural tendencies, and other circumstances will require different approaches. I can’t see any possibility of a plan like Doerr’s being translated into a uniform set of marching orders across the globe. I don’t imagine that this is Doerr’s expectation, either.

None of that is the point. As Eisenhower famously said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” There is immense value in a detailed plan for mitigating climate change:

It offers hope. The mere fact that it’s possible to articulate a coherent plan, tells us that bringing emissions under control is in fact achievable.

It raises expectations. This is the flip side of hope: if we can halt greenhouse gas emissions, then we don’t need to accept excuses to keep polluting.

It exposes challenges. With a plan laid out in clear detail, we can review to see which goals look hardest to achieve, and focus additional resources toward those goals.

It sharpens tradeoffs. This is a big topic, so I’ll devote the next section to it.

It provides a benchmark to evaluate progress. Are we moving quickly enough? Where do we need more resources?

Tradeoffs

If current emissions are 59 billion tons of CO2 (or equivalent) per year, and (per Doerr) we plan to pull 10 Gt/year out of the atmosphere, then that leaves us needing to reduce emissions by 49 Gt/year. We could eliminate any 49 of the 59; the atmosphere doesn’t care where CO2 comes from, it only cares how much there is.

Doerr proposes a specific breakdown, but there’s nothing magic about it. We could, say, aim to reduce air travel emissions a bit more, and relax a bit on agricultural emissions. In fact, there are a lot of choices for where we find those reductions:

By sector (transportation vs. agriculture) and sub-sector (trains vs. ships)

By country and region

By use case (individual-owned cars vs. corporate fleets; urban commute vs. off-grid roaming)

By time (e.g. get really aggressive in the next few years so that we don’t need to push as hard in the 30s and 40s)

Greening (e.g. convert airplanes to hydrogen) vs. reducing (discourage travel) vs. replacing (promote rail as an alternative to flying)

Reducing emissions vs. capturing more CO2 from the atmosphere

Accept more / less warming in exchange for less / more cost and economic disruption

We will need to make intelligent choices. In a region with lots of solar power but low population density, electric cars might make sense; in a dense region with not much room for solar, it might be better to invest in (green) public transit. By articulating a cohesive plan, Doerr provides a framework we can use to flesh out these choices.

What’s Missing

I found the actual experience of reading Speed & Scale to be frustrating. The level of detail – “Freight (Medium & Heavy Trucks)” goes from 2.4 Gt / year to 0.8 Gt / year – suggests an intensive level of research and analysis. But very little of that supporting work appears in the book, making it difficult to evaluate. Why is the target 0.8 Gt / year, and not 0.9 or 0.3? What will be needed to achieve that target? Are new technologies required? Significant changes to policy? Are we on track to get there?

As someone interested in helping to mitigate climate change, this book does little to help me understand where to focus. Where are the greatest needs? Which of these targets is most at risk? Doerr clearly wants this book to inspire action on climate change, and yet it is strangely bereft of specific calls to action. If you are an activist, investor, entrepreneur, or just a concerned citizen, this book will leave you wanting to dive in but with little idea where to do so.

It does seem that there are plans to publish a “tracker” showing the progress toward each goal. From https://www.producthunt.com/posts/speed-scale:

@hector_perez_arenas Yes! We will be updating speedandscale.com to show the current state of the Speed & Scale OKRs. Our hope is to launch that version in January. We want it to live as a public tracker. From there...we'd love to use that as a springboard for the community to share their OKRs. 🙏🏾

But this seems like only a small step. Measured progress toward end goals is a lagging indicator. I imagine that if we make great progress on “Freight (Medium & Heavy Trucks)” next year, emissions might drop from 2.4 Gt / year to 2.39 Gt / year, as the necessary technologies and products start to find their way into the market. Distinguishing that good scenario from the no-progress scenario, based solely on year-end emissions, seems impossible. A tracker is helpful, but far from sufficient.

Should You Read it?

Honestly, it’s hard for me to say. I did mention that this is my first book report in 40 years. I feel like I’d need to go back and read it a second time with an eye toward this question.

If you’re looking for a comprehensive, optimistic-but-practical overview of the field, grounded in science and economics but not overly technical or detailed, this may be the book for you. As a reader, I found no value in the actual plan – the sector-by-sector targets. But this is a small portion of the book. Most of the material consists of sector-by-sector overviews, stories, and contributor essays, and I found this to be well done. If you’re past the introductory stage, and feel like you have at least a basic grasp of all the major emissions sectors, the book may be unnecessary reading.

As a comparison, I also recently read Electrify: An Optimist's Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future, by Saul Griffith. Electrify is also an action plan for mitigating climate change, and may be more accessible. However, I also found it to be less comprehensive and sometimes repetitive. Speed & Scale is drier, but more comprehensive, practical-sounding, and actionable. Ultimately I found it to present a more compelling case.